To all my loved ones, cheers ♥

Theme adapted from orderedlist

Types of Operating System Kernel Structures and Virtual Machines

24 May 2021 - Guanzhou Hu

This post summarizes the different types of operating system kernel structures (kernel models) and virtual machine structures. Apart from the best-known monolithic kernel model, OS kernels may also take the form of microkernel, semi-microkernel, exokernel, kernel bypassing library for certain subsystems, or disaggregated kernel. Virtualization of OS environment as a whole (i.e., virtual machines) has become popular with the rapid trend towards cloud computing. Virtual machines can be categorized as type-1a vs. type-1b vs. type-2.

OS Kernel Structures

An operating system kernel is the composition and collaboration of the following pieces:

- Core functionalities

- Architecture-dependent: booting, interrupts, specific ISA interfaces

- Concept of “process”, basic inter-process communication (IPC)

- CPU scheduling

- Memory management

- Subsystems

- Storage subsystem: file systems, naked databases

- Network subsystem: networking protocol stacks

- Device drivers: providing access + scheduling per external device; External devices may include:

- Block devices used by the storage subsystem

- Network cards used by the network subsystem

- Various peripheral devices such as as sound cards and graphic cards

- Specialized computing devices such as GP-GPUs, TPUs, and FPGAs

A complete operating system typically include the following programs running as privileged processes, with the support of the kernel, to provide a reasonable user interface:

- Shell language + terminal

- GUI desktop environment

- Task monitors, other daemon monitors

Then, user application programs run as user-level processes with the support of above-listed functionalities. Different OS kernel models distinguish from each other in where they put each of these functionalities, how they implement them, and how they hook them together.

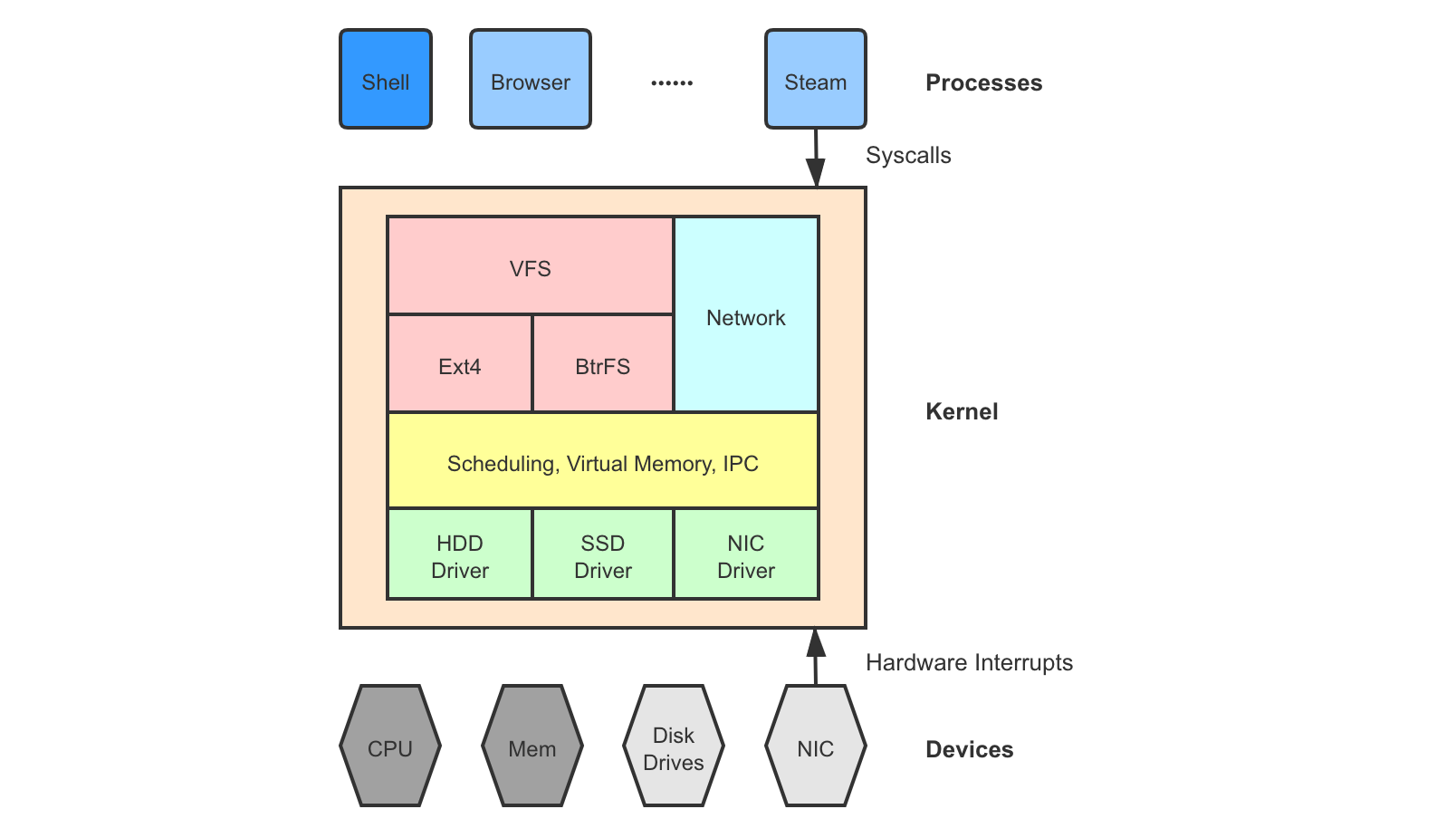

1. Monolithic Kernel

As the name suggests, a monolithic kernel encapsulates everything into a whole. A monolithic kernel often takes a layered structure, where each layer is based on the correctness of the lower layer and adds in a level of abstraction to be used by the upper layer. All application programs run as processes on top of the kernel.

Not to be mistaken, the kernel itself is NOT a running entity. It is just a big codebase of registered handlers for interrupt events: software interrupts issued by application processes (syscalls) or hardware interrupts from devices (e.g., timer interrupts that trigger scheduler decisions, etc.). You can think of it as a static code stack that a process will have access to when it switches to privileged mode. Only the processes are running entities that take up CPU and memory resources to do work. Upon an interrupt, they switch to privileged mode to execute some kernel logic such as accessing a shared resource through a syscall or yielding to the scheduler context on a timer interrupt. There are exceptions, of course, for example at booting or where we have special kernel threads doing background work that do not belong to any specific process.

Monolithic kernel is the most classic kernel model originating from the very early OS prototypes such as THE 1 and UNIX 2. Most of the recent mainstream OS platforms are based on a monolithic kernel: BSD, Linux 3, OS X, and Windows. A monolithic kernel is very compact and highly efficient, meanwhile, hard to develop (low code velocity) and less flexible.

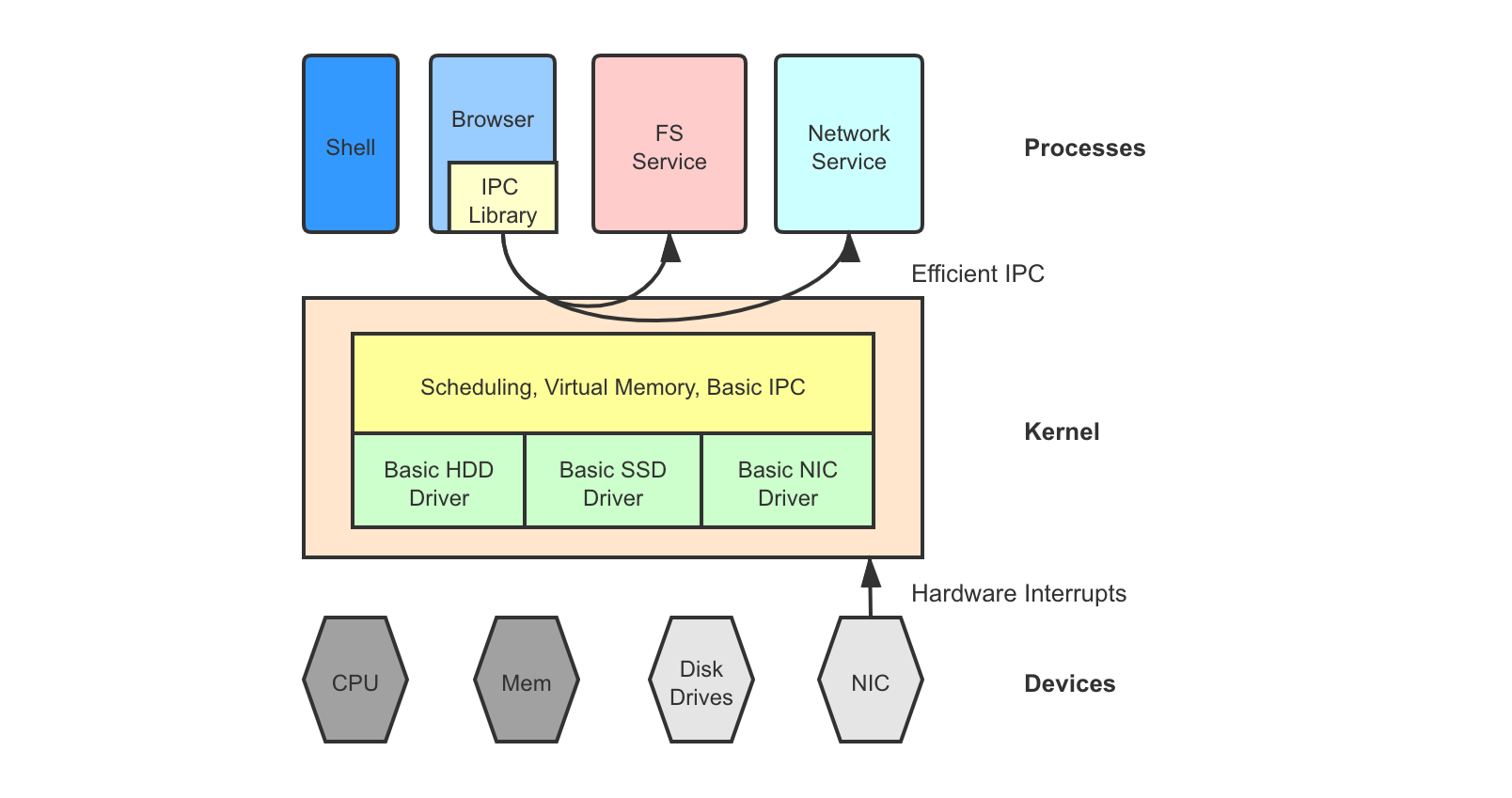

2. Microkernel

A microkernel, in contrast, implements only the core functionalities such as process isolation, CPU scheduling, virtual memory, and basic IPC mechanisms. Each of the subsystems run as a dynamic process, often called a service, which is just like a user process listening on IPCs but may have higher privilege and scheduling priority. These services often have dedicated direct access to their corresponding hardware resource.

Say a user application wishes to fetch the next incoming network packet. Instead of making a syscall down to the kernel network stack, it makes an IPC through the kernel into the networking service. The service process then reacts to the IPC request. Think of it as the client-server communication model.

Examples of microkernel include MINIX 4 and the L3/L4 microkernel family 5. Microkernel makes it easier to develop/debug kernel subsystems as developers are almost just writing user programs. Code is also more modularized and less entangled. However, microkernel performance is very sensitive to the efficiency of IPCs, making it generally less performant than monolithic kernel.

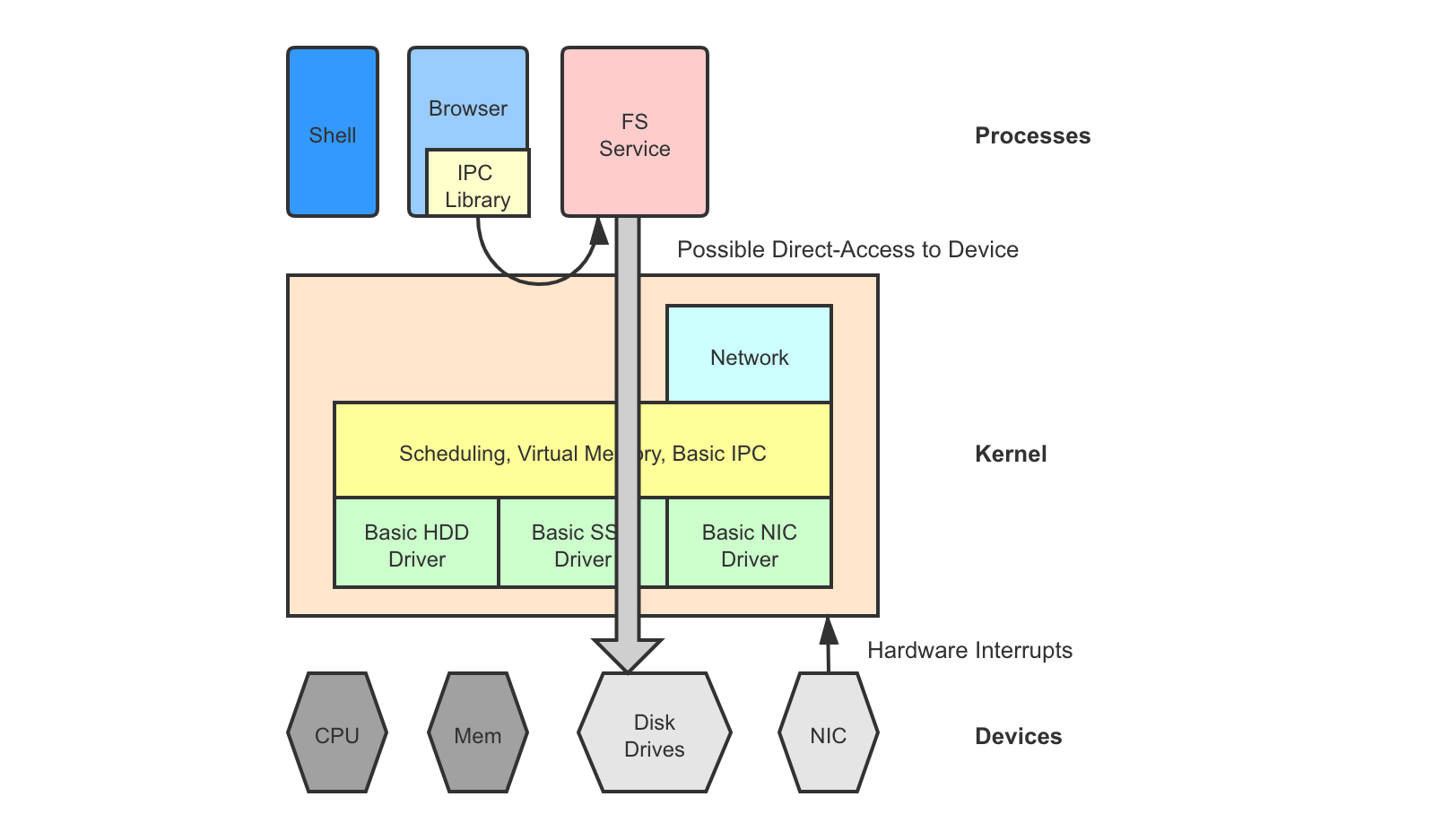

3. Semi-Microkernel

Sometimes we only want to move a subset of the subsystems up as processes and keep everything else still in the kernel. For example, if we are targeting at applications with special storage requires and want to easily develop a custom scalable file system, we can have the file system running as a process while the device drivers and the networking stack still in the kernel.

Examples of such semi-microkernel include FUSE 6 for user-space file systems and Google Snap 7 for user-space networking. Our group also has an upcoming paper on this one. Semi-microkernel is a compromise between monolithic kernel and microkernel.

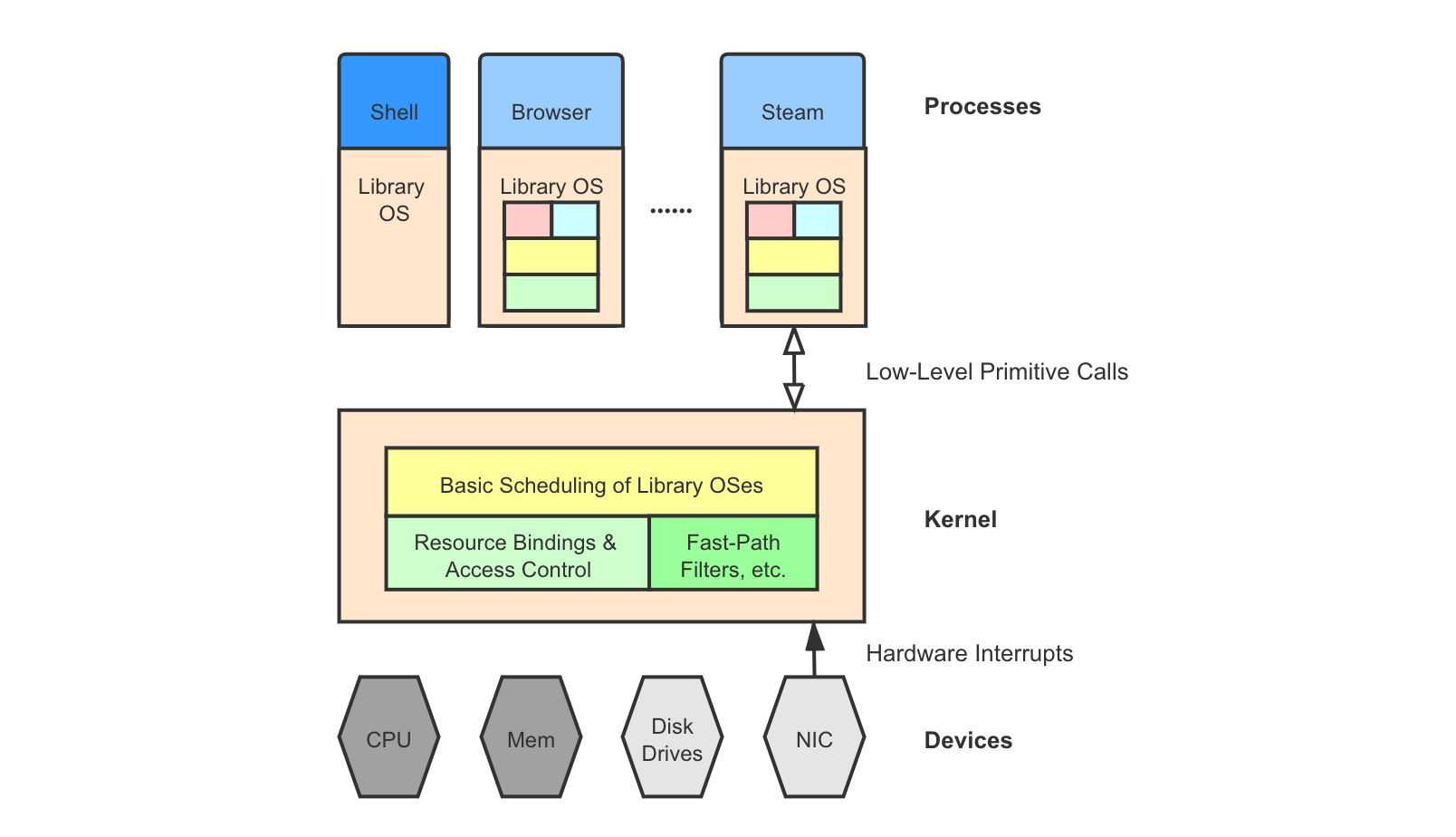

4. Exokernel

Exokernel takes a more aggressive approach by moving not only the subsystems but also most of the core functionalities into each application, essentially linking each application program against a custom library OS. The kernel itself becomes minimal. These library OSes share hardware resources through a more primitive, coarser-grained interface than traditional syscalls.

Exokernel is introduced by this paper 8 and it also inspires the idea of virtual machine hypervisors. Exokernel calls share much similarity with hypercalls in type-1 virtual machines, which we will talk about in the next section. Exokernel allows developing highly-optimized kernel implementations customized for each different application, but makes it harder to coordinate and schedule around multiple application processes.

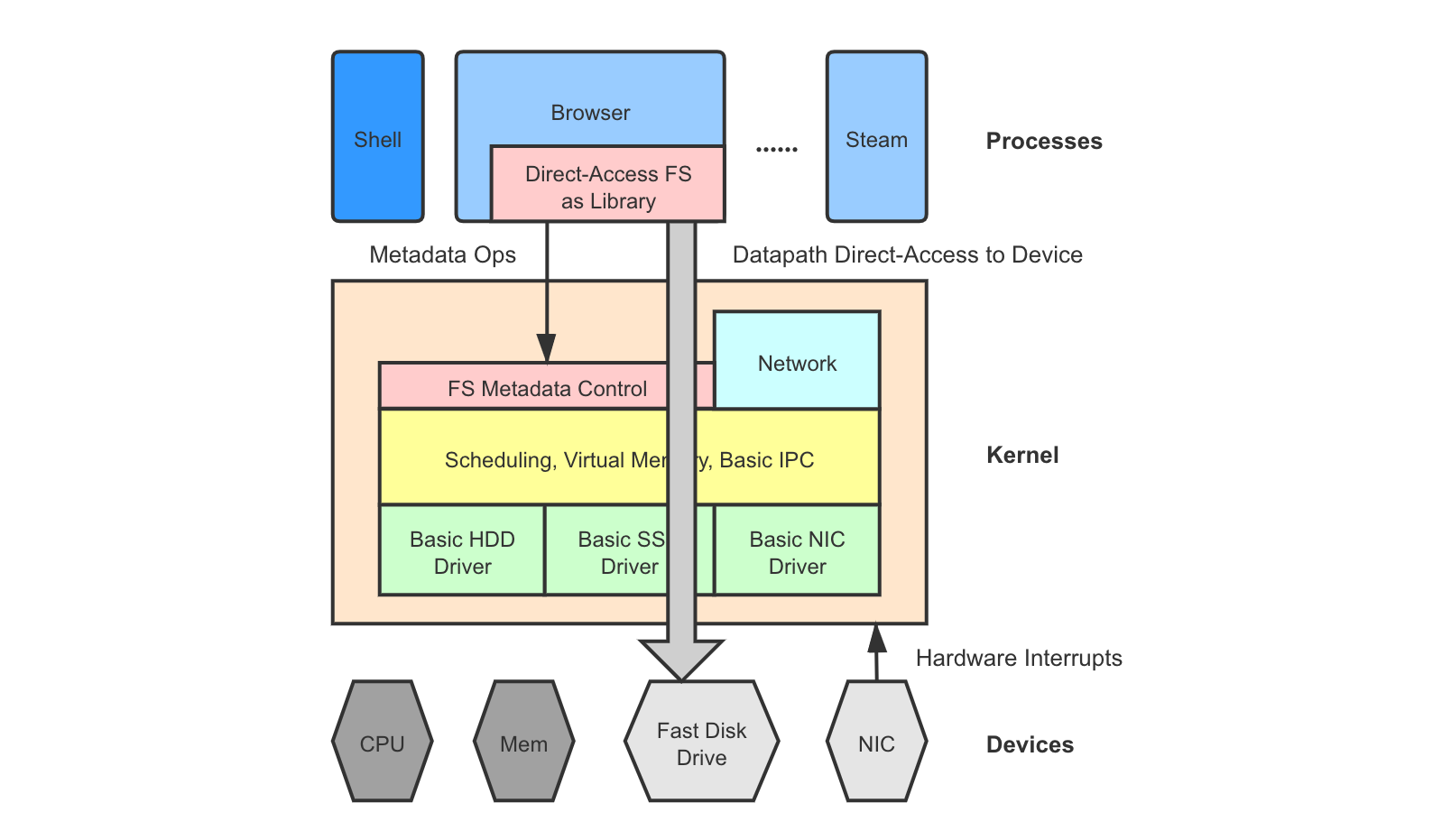

5. Kernel Bypassing (Direct-Access Library for Certain Subsystems)

With the evolution of storage and networking devices, the overhead of kernel software stack is becoming much more significant. Sometimes, we want a lighter-weight storage/network subsystem tuned for an application and granted direct access to a modern device, so that it bypasses the centralized kernel stack for better latency.

Unlike the microkernel case, the “moved-up” part does not run as a separate processes (which means still a centralized component able to perform scheduling and performance isolation), but instead is written as an application library linked into application processes (which means multiple processes invoke the subsystem logic independently, with less performance isolation).

Much research effort has been put into this field in recent years. Examples include Arrakis 9, Strata 10, SplitFS 11, Twizzler 12, and many more. I think of direct-access libraries as a compromise between monolithic kernel and exokernel, though some of the research prototypes have not considered the sharing and scheduling problem among processes yet - they just grant the library full control over the device on the datapath.

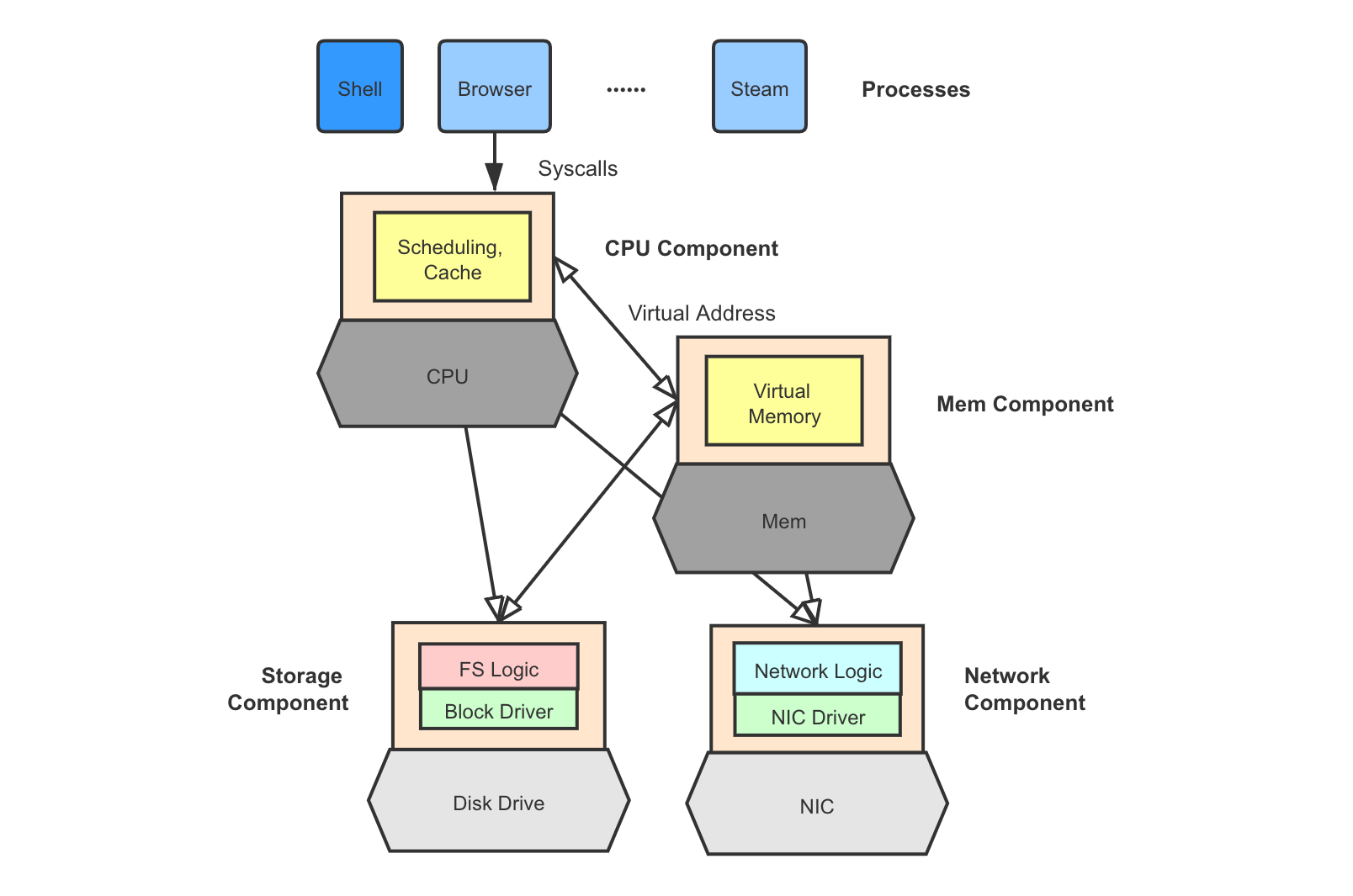

6. Disaggregated Kernel

Hardware devices are getting smarter and are equipped with “small computers” on board. SSDs have FTL controllers running inside with its own RAM. Other devices such as network cards have the same trend too. A disaggregated kernel takes advantage of the computing power on each device and distributes the kernel component for a device onto the device itself. A smart memory chip may run a memory management component and a disk may run a full storage stack + driver. This moves the kernel closer to the hardware (, in contrast to closer to the applications, as in microkernel and exokernel).

Kernel disaggregation brings flexibility, elasticity, and fault independence. A DRAM failure in other kernel models means the entire machine goes down, while a failed memory component in disaggregated kernel does not affect the correct functioning of all other components. The downside is that it is essentially turning an OS kernel into a heterogeneous distributed system, making it much harder to develop, maintain consistency, or yield high performance.

The best example of disaggregated kernel is LegoOS 13.

There are also efforts in exploring writing an OS kernel in higher-level languages with runtime garbage collection. Biscuit 14 does it in Go.

Virtual Machine (VM) Types

In the cloud computing era, it becomes increasingly interesting and useful to be able to run multiple OS environments on one physical machine. The virtual machine technology uses a hypervisor (or virtual machine monitor, VMM) to simulate/emulate hardware resources and to coordinate across multiple guest OSes. Virtual machine solutions are often categorized as follows.

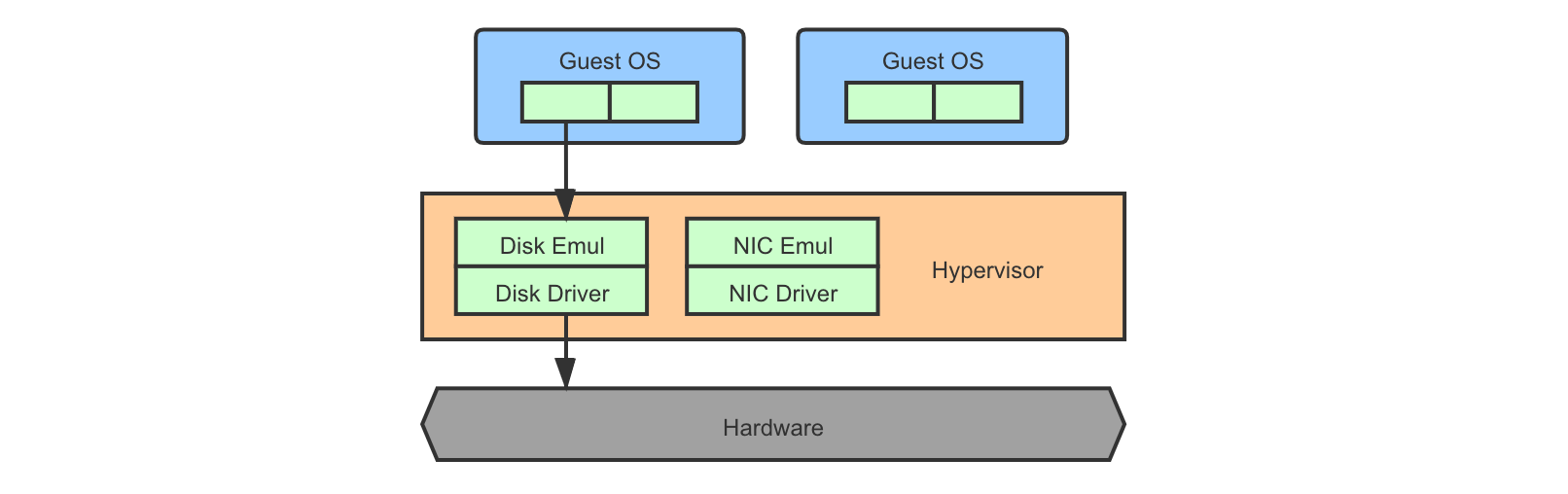

Type-1a (Hypervisor Has Full Control & Drivers)

The hypervisor runs directly on and has full control over the hardware, and the device drivers are also implemented inside the hypervisor. Guest OS does not need to be modified, as long as it hooks with the emulated device interfaces.

This approach is the most straightforward but requires a strong hypervisor that provides complete device driver emulation. This model originates from the work of Disco 15 and examples include VMware ESX/ESXi 16.

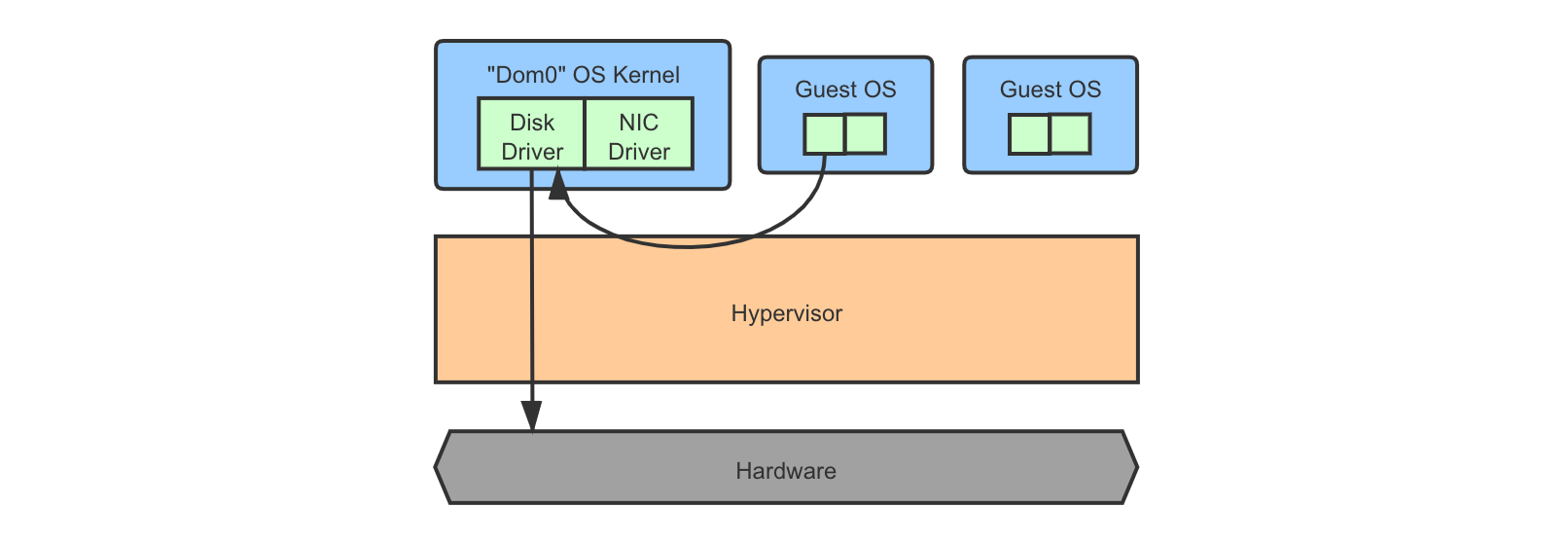

Type-1b (Hypervisor + Dom0 Kernel for Drivers)

The hypervisor runs directly on and has full control over the hardware, but device driver implementations are provided by a special domain-0 (Dom0) OS. Other guest OSes are called domain-U (DomU). Guest kernel device requests are redirected to the Dom0 kernel.

Typically, the DomU kernels may need a few modifications to be able to fit in this model. This characteristic is called para-virtualization, meaning that it is OK to apply small modifications to the guest kernels and they do not need to work out-of-the-box as if without virtualization.

Sometimes, there are even special, minimal OS kernels written just to be used as these DomU kernels in type-1b VMs. They are called “unikernels”.

Examples of type-1b hypervisors include Xen 17.

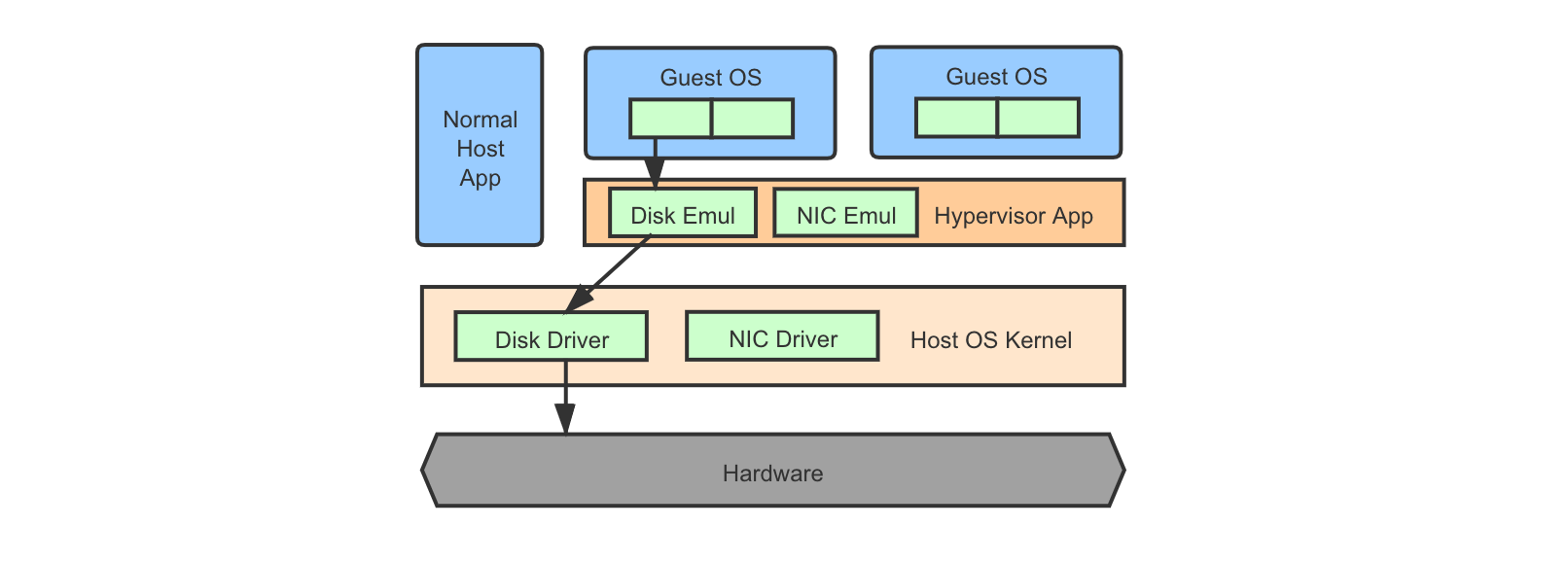

Type-2 (Hypervisor as an Extension to Host OS)

The hypervisor is just a software package/kernel module extension running on a host OS, which emulates hardware platforms for running guest OSes.

Examples include VMware Workstation 18, Virtual Box 19, and QEMU (on Linux, possibly with KVM support) 20 21.

Pure software emulators deliver poor performance as they add in an expensive layer of abstraction. Modern hypervisors, whichever type it belongs to, often take advantage of dedicated hardware support to provide more efficient virtualization if the guest ISA is the same as the host machine (e.g., running x86-64 VMs on an x86-64 platform).

For type-2 use cases, some host OSes like Linux also provides kernel-based virtual machine (KVM) support which allows emulators like QEMU to run more efficiently and “natively”.

References

-

THE: https://www.cs.utexas.edu/users/dahlin/Classes/GradOS/papers/p341-dijkstra.pdf ↩

-

MINIX: http://www.minix3.org/ ↩

-

L3/L4 Family: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/L4_microkernel_family ↩

-

FUSE: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Filesystem_in_Userspace ↩

-

Exokernel: https://cs.nyu.edu/~mwalfish/classes/14fa/ref/engler95exokernel.pdf ↩

-

Arrakis: https://www.usenix.org/conference/osdi14/technical-sessions/presentation/peter ↩

-

Strata: https://www.cs.utexas.edu/users/witchel/pubs/kwon17sosp-strata.pdf ↩

-

SplitFS: https://www.cs.utexas.edu/~vijay/papers/sosp19-splitfs.pdf ↩

-

Twizzler: https://www.usenix.org/system/files/atc20-bittman.pdf ↩

-

LegoOS: https://www.usenix.org/conference/osdi18/presentation/shan ↩

-

Biscuit: https://www.usenix.org/conference/osdi18/presentation/cutler ↩

-

Disco: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download;jsessionid=1473D91F21DBDF43FEF78259A24F0F2D?doi=10.1.1.103.714&rep=rep1&type=pdf ↩

-

VMware ESXi: https://www.vmware.com/products/esxi-and-esx.html ↩

-

Xen: https://xenproject.org/ ↩

-

VMware Workstation: https://www.vmware.com/products/workstation-pro.html ↩

-

Virtual Box: https://www.virtualbox.org/ ↩

-

QEMU: https://www.qemu.org/ ↩

-

KVM: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kernel-based_Virtual_Machine ↩

Comments welcome! 😉