To all my loved ones, cheers ♥

Theme adapted from orderedlist

Decentralized Trust: Essential Ideas Behind Blockchain Technology

05 Jul 2020 - Guanzhou Hu

The name Blockchain has been a hot word in the past few years. Despite the controversy behind some of its applications such as virtual currency, blockchain itself is actually an appealing proposal towards decentralized trust over the Internet. It is worth looking into when studying modern distributed systems, especially as a good example of the design and implementation of decentralized systems.

Centralized Trust vs. Decentralized Trust

Many online services over the Internet are built upon centralized trust, for example, an online banking server (or possibly a set of distributed servers) maintaining and managing all customers’ accounts and transactions, or a centralized CA signing web certificates. While this is a natural way of modeling “trust”, centralized trust does require all participants to fully rely on the integrity of the central service in order for the whole system to work. This often exposes the central service as a single point of failure in the sense of both trust and availability.

Decentralized trust describes a model where all participants of the system are equal and they all work together to somehow agree on a global consensus, without any central service. The “consensus” can take different forms for different applications - can be a global total ledger for virtual banking or a complete list of domain -> pub_key mapping for decentralized certificates.

Blockchain Overview

Blockchain1 is the first successful design (and by now the only one AFAIK) of such a decentralized trust architecture. It forms the global consensus as a chain of signed blocks representing the complete global history. Each participant node holds a copy of this whole chain. When a participant wants to make an update to the consensus, it signs a new block describing the modifications, appends it to its copy of the chain, and propagates the new chain to others on the network in a peer-to-peer manner. At its essence, three core ideas support its design:

- Chain of signed blocks as the global history as the consensus;

- Longest chain protocol to resolve conflicts;

- Proof-of-work + \(k\)-deep confirmation to ensure a high-level of correctness.

Decentralized apps (DApps) built upon blockchain architecture tend to scale flexibly by its distributed nature. However, that does not mean blockchain brings higher performance. In contrast, due to the need to maintain decentralized integrity, blockchain exposes a ridiculously high latency to operations and often delivers very poor throughput compared to highly-optimized centralized services. It also does not guarantee 100% confidence of behaving correctly and the integrity guarantee is very easy to break if a malicious participant holds nearly 50% of total computing power of all participants.

这段不知道怎么用合适的英文表达:Decentralization 更多是一种去中心化和独立化的 Geek 情怀在里面,个人认同但不认为现有的 Blockchain 设计能支持实现大规模的 Internet infrastructure,至今也只有少数原型被实现,暂未成大器。作为对比,另一个有此情怀的技术——Onion Routing & Tor——至少做出了点能用的东西 2 3。

Despite, decentralization is still one of the future directions of distributed systems and worth further research.

1. What to Agree On: Chain of Signed Blocks as the Global History

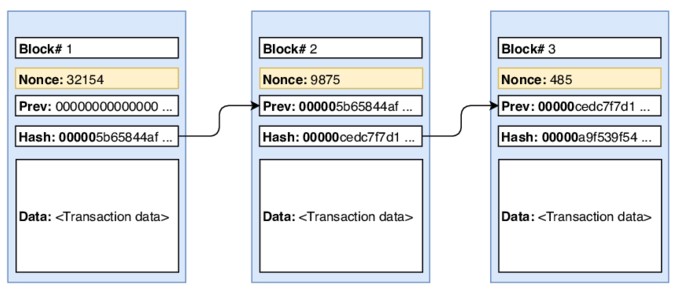

The first and the most fundamental piece of Blockchain is representing the global history as a chain of signed blocks. Initially, all participants start with a dummy block, indicating an empty history. When a participant \(P\) wants to make new modifications to the global consensus, it batches its modifications into a new block and appends it to the end of the chain. A block consists of three significant components1:

- The proposed modifications;

- Hash of the previous tail block in chain;

- \(P\)’s signature covering the above two.

The most important thing here is that each block is now linked to its predecessor through the hash tag, forming a hash chain. We assume using a cryptographically-safe hash function here, which means it is not invertible and is almost impossible to find a different plaintext which gives exactly the same hash value. Once a chain has been formed, changing any bit anywhere in the middle of the chain will break subsequent hash links and, therefore, fail the hash checks. Thus, for any such chain, we can simply traverse through it from beginning to end to verify that it is a valid history, i.e.,

- Chain starts with initial block and all hash links are not broken;

- Every block is correctly signed by its proposer;

- There is no single timepoint throughout the history that violates application-specific rules (e.g., balance cannot go below $0).

We represent the global consensus as a bare history of changes instead of states (e.g., a complete transaction history instead of a mapping from accounts to balances), since the latter one only represents a snapshot at the end timepoint and cannot offer a way for nodes to achieve agreement, as we show in the next section. This history is called a global ledger. This ledger is the consensus, i.e., what we want all nodes to agree on. For a node to reason about the current state of the system, it needs to traverse through the history and build a snapshot.

Figure from here.

2. How to Achieve Agreement: Longest Chain Protocol

Once the new block has been added to \(P\)’s local chain, it propagates the new chain to all the other peers by means of flooding or other P2P networking mechanisms. A peer, upon receiving a new chain from others, first verifies that it is indeed a valid history. If so, it adopts the new chain.

Problems arise when many participants are generating new blocks and propagating them over the network concurrently, resulting in many forking chains. To resolve conflicts, a node always adopts the longest chain it has seen1. Yes, it is still possible that multiple versions of the chain forking forever and always having the same length, making participants to permanently agree on different global history, but with proof-of-work described in the next section, the chance is relatively low and in the long-term nodes will converge.

A proposed block is considered to be confirmed by a node when it stays in its chain for a desired amount of time, and only by then the operations record in that block are considered “actually executed”. If a block fails to confirm, the operations are considered “failed” and the proposer might retry later or just give up.

3. Reduce Forking & Private Double Spending: Proof-of-Work & Confirmation Depth

As we may have noticed, if all participants keep adding new blocks very quickly, forking is unavoidable and is very likely to never converge. Worse, there is also the problem of private double spending: A malicious participant \(A\) can send $10 to \(B\), wait until that block is confirmed meanwhile forking the old chain with sending $10 to \(C\) and keeps adding blocks to this new chain in background. After \(B\) has confirmed receiving $10, \(A\) then propagates the new chain (which will be much longer) and everyone will finally agree on the new chain since it is longer. So, \(A\) can effectively spend the same $10 to both \(B\) and \(C\), with both of them confirming reception.

To overcome this and make the whole system usable, Blockchain deliberately sacrifices performance for high-level confidence of correctness with proof-of-work1. It adds a fourth requirement to a newly-added block that:

- Adds a random number (salt, nonce) to the block and computes the hash of the block itself, and requires that the final hash result must have \(z\) bits of preceding

0s; If not, just try a different salt until the requirement is satisfied.

Proof-of-work requires a node to spend a decent amount of computing power and time to produce a valid block. This procedure is called mining. Thus, the pace of how often a new block appears in the system is deliberately controlled by setting a desired \(z\) difficulty value. (For example, Bitcoin sets it to \(\approx\) 6 new blocks / hour.) Forking is thus greatly reduced. Also, unless the malicious attacker holds a majority of total actual computing power of the whole system (quite unlikely in real-world cases), there is a very low chance for the attacker to carry out a successful double spending attack.

A block is confirmed when it stays in the longest chain until there are \(k\) new blocks after it, i.e., it is \(k\)-deep in the globally-agreed chain. (Take Bitcoin as an example, confirmation delay is around 10 minutes to even a whole day, which seems unreasonably long.)

Blockchain is indeed trading throughput and latency for correctness - and I don’t quite agree on this choice. Say the mining rate is \(f\):

\[\begin{cases} \text{Throughput } &\propto f \\ \text{Latency } &\propto \frac{1}{f} \\ \hline \\ \text{More forking } &\propto f \\ \text{Easier double spending} &\propto f \end{cases}\]Unresolvable inhererent controversy!

Decentralized Applications (DApps)

Examples of DApps include4:

- Virtual currency: Bitcoin, Ethereum, …

- Internet naming infrastructure: Blockstack5

The true identity of Nakamoto - the first to solve the private double-spending problem and author the Bitcoin paper - is still a myth as of today. Many have claimed but none provided convincing evidence. See here. This is kind of interesting.

References

Comments welcome! 😉