To all my loved ones, cheers ♥

Theme adapted from orderedlist

Consistency Models for Distributed Replicated State Machines

23 May 2020 - Guanzhou Hu

NOTE: this post is outdated and contains some of my early misunderstandings, so please read skeptically. A new post series on understandable categorization and in-depth analysis of consistency models is coming out soon, which will serve as the theoretical foundation of my ongoing research.

Replicated state machine is a common design of a distributed system to achieve fault-tolerance against fail-stops. Consistency among distributed replicas thus arise as a crucial problem. People have defined different levels of consistency models throughout distributed systems research. Some of them are strong and easier to reason about and program with, while others weaken the constraints to pursue higher performance.

Replicated State Machines

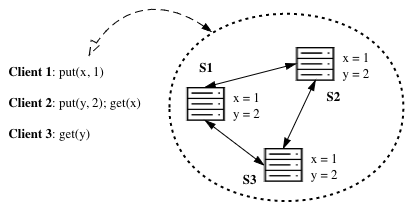

Consider a classic key-value store scenario. To provide fault-tolerance, data is replicated over multiple server nodes and coordinated (using a consensus algorithm such as Paxos or Raft, or a coordination service such as ZooKeeper, or other models with weaker consistency).

We assume nodes can fail independently at any time (losing temporary states) and the networking among clients and server nodes is unreliable (nodes may be partitioned, packets may drop, and may arrive out-of-order). We do require that persistent storage is reliable and there is no malicious modification of messages (no Byzantine failures).

Clients talk to a distributed KV store service hoping that it performs just as a single machine executing orders serially. This is the ideal case under strong consistency (linearizability). Different designs of how data gets replicated expose different levels of consistency. Strong consistency acts just like a single machine and is easier for application programmers to reason about, but it mostly means limited scalability and poorer performance. Weaker consistency models are typically more scalable, has lower latency, and much higher throughput.

The “CAP” Theorem

The CAP Theorem1 states that every distributed replicated state machine cannot achieve all the following three properties at the same time.

- (Strongly) Consistent: satisfies linearizability, see the next section;

- (Always) Available: requests always receive a response;

- Partition-tolerant: works under arbitrary network partitioning.

The wikipedia page clearly states why. This theorem illustrates that when network partitioning is possible, we must tradeoff between consistency and availability.

Consistency Models

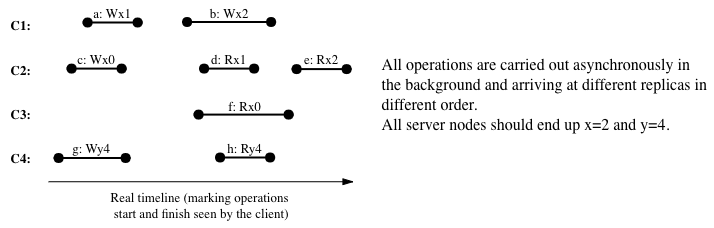

Consider a distributed data store system with two kinds of operations: v = read(x) (Rxv) and write(x, v) (Wxv). A partial rank of strictness of common consistency models, based on the COPS paper by Lloyd et al.2, is:

Strong (Linearizability) > Sequential > Causal > Eventual.

1) Strong Consistency (Linearizability)

A data store system is strongly consistent (linearizable) if it offers:

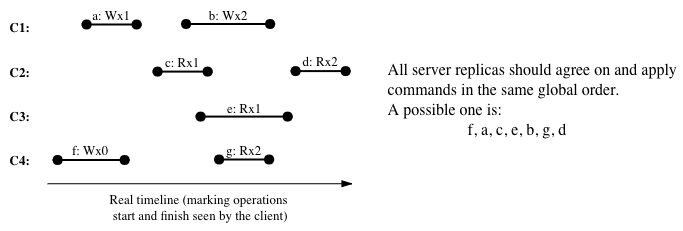

- Global ordering: all replicas must agree on the same global serial order of all operations; value of a global variable is up-to-date with the order – every read operation reflects the most recent (up to itself in the order) value written to that variable by previous writes.

- Real-time property: the global order must satisfy the real-time property – if operation \(b\) starts after the ack of operation \(a\) in (real-world physical) time, i.e., operation \(b\) is issued after someone receives response for operation \(a\), then \(a < b\) (\(a\) is ordered before \(b\)) in the agreed ordering.

- Causality: from each client thread’s perspective, the ordering of operations issued by itself must be maintained in that global order, i.e., the global order should be the sequence of its own operations interleaved by other thread’s operations. Causality is implied by the real-time property, because a read by a thread can only start after any previous write by this thread has been acked.

Intuitively, strong consistency requires a distributed system to act as if it is a single machine without replication - all clients are virtually talking to a single-core node in some serial order. If a read is issued by some client after a write has been confirmed by perhaps another client, and there are no other writes getting confirmed in this window, then we expect that read to reflect the written value. This property is desired when data must be synchronized in real time and stale data is strictly not allowed. Reads must return the global newest value among all nodes. This guarantee makes it very easy for application programmers to reason about how the system behaves.

Examples include all consensus algorithms such as Paxos3 and Raft4, and some other replication techniques such as ZooKeeper (ZAB) and chain replication (CR). They typically record client requests (both R and W) into log entries, replicate and agree on a global log sequence, and then apply the log entries in order. Many (I would say most) systems are built upon these log-based models to provide a linearizable history as long as a majority of the nodes are alive and connected. The price is that each operation has a long latency-to-apply and overall throughput is low.

2) Sequential Consistency

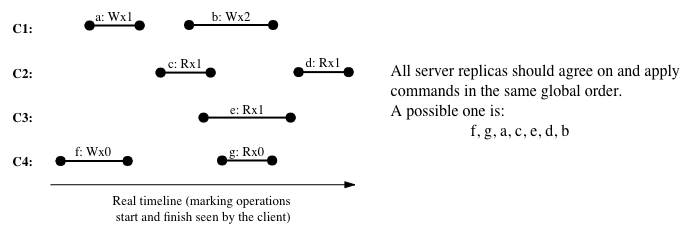

A slightly weaker consistency model with respective to strong consistency is sequential consistency. It still requires all clients to agree on a global ordering, but relaxes the real-time property and instead only requires that, for each client thread, its operations happen in the same order as in the global ordering, i.e., causality.

In brief, sequantial consistency requires:

- Global ordering

- Causality

This is a weaker level of consistency as it removes the “real-time” constraint of strong consistency, which enforced ordering between operations across threads that do not overlap in time. Sequential consistency could happen if say a system acks a write earlier than the write has been accepted by a majority.

3) Causal Consistency

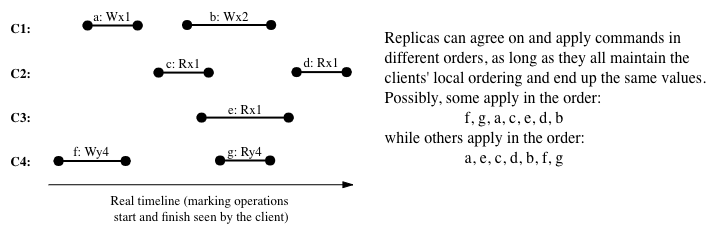

Causal consistency further decouples different client threads and only requires that, for each client thread, its operations happen in order. No explicit guarantee is placed upon how operations reflect results written by other clients. We do not require all replicas to agree on the same global order, as long as they end up with the same values in database (at the end of day, after all operations done).

In brief, causal consistency requries:

- Causality

Causally consistent systems often encode operation dependencies within each client thread, and on each replica, apply an operation when its dependencies have all been applied. Since only a local order is forced, causal consistency allows a system to be available under network partitioning. If one client thread only interacts with its nearest replica, causal consistency enables local read - read returns the local replica’s value and does not have to wait.

Causal consistency is widely criticized for its known cascading dependency wait issue. Such programming model is also not straightforward enough - programmers must arrange their code to maintain the “causality” of database requests. (Consider a scenario where you update profile content together with an access control list. When you are adding someone into the ACL, should update content first, so that as soon as they see you accepted their friend request, they see your up-to-date profile. However, when you are revoking someone from the ACL, should update ACL first, so that they cannot notice your latest profile change.)

4) Eventual Consistency

The weakest consistency guarantee for a distributed replicated system is eventual consistency. Reads will eventually reflect the result of all writes and replicas eventually contain the same values for variables. Yet, reads are allowed to return temporary stale values and out-of-order intermediate values.

In brief, eventual consistency does not enforce any global ordering of operations, real-time property, or causality.

Eventual consistency is very useful for many web services, where temporary stale data is not a big deal, but scalability and performance are significant. Because we no longer fear out-of-order writes at replicas, with eventual consistency, we can use cached local write + background pushing. Writes can now return immediately without waiting, just as reads.

Because all replicas still need to agree on a consistent value at the end of day, such systems often involve a conflict resolution mechanism when a replica receives concurrent writes to the same variable. The policy might be “last writer wins” with Lamport clock timestamp5, or some ad-hoc mechanisms like “taking the union”.

Examples include AWS DynamoDB and Cassandra.

References

Comments welcome! 😉